Without Walther Hensel, I would not have become a publisher

The founding of Bärenreiter-Verlag

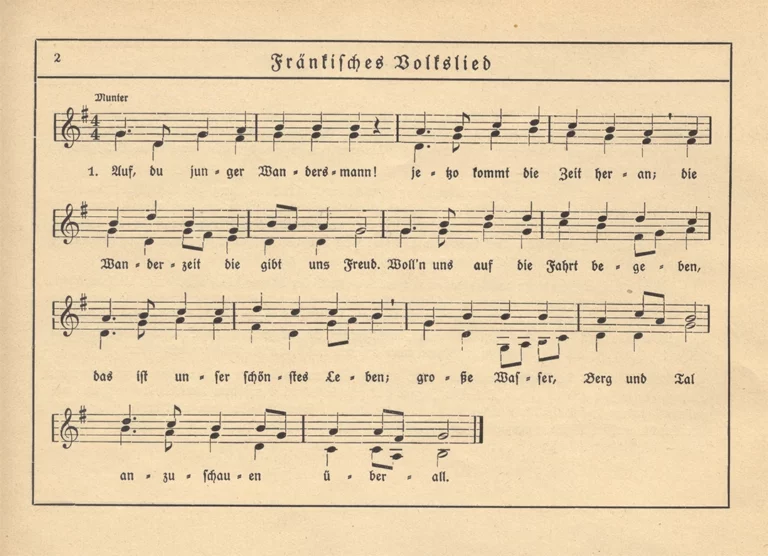

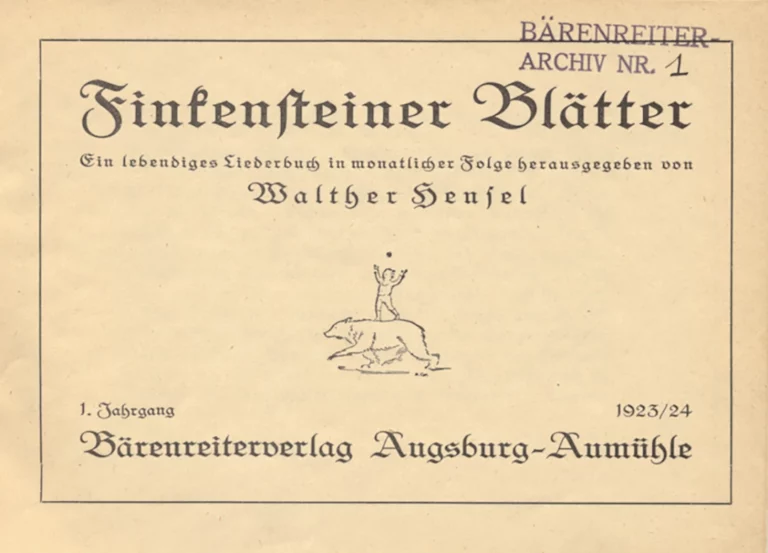

When Karl Vötterle took his first steps into the world of publishing in September 1923 with the first issue of the Finkensteiner Blätter, an eight-page booklet of folk songs, one thing was certainly not on his agenda: to claim a place alongside the long-established publishers of Leipzig and Mainz by founding a world-class music publishing house. The circumstances alone spoke against such ventures: the First World War had brought Germany to its knees; eye-watering reparation payments and hyperinflation were placing an unprecedented burden on the country; Germany’s young democracy was under attack from both the right and the left; politics and society were teetering on the brink of the abyss. Taking a major economic gamble in such a situation would have been utterly foolhardy. But Karl Vötterle was concerned with something else in any case: the founding of his publishing house was motivated by the insight that “we all share equally in the hardships of our time and desire to do equally constructive work”, as he wrote in 1924, looking back on his first year of publishing.[i] There was a need both to overcome the trauma of the Great War and the humiliation associated with it as well as to confront bourgeois musical culture, which was seen as decadent, split between sensationalist entertainment and intellectual appropriation – ultimately, there was a need to find the “source” of the “renewal of trust in ourselves”.[ii]

The “we” Vötterle refers to were the followers of the Singbewegung or “singing movement” around the charismatic Sudeten German folk song collector and singer Walther Hensel. Vötterle had organized two song recitals for Hensel in Augsburg in the spring of 1923 and had immediately fallen under the spell of his voice. “We” also included the participants of the first “singing week” led by Hensel in Finkenstein near Mährisch Trübau (today’s Moravská Třebová) in Czechoslovakia in July 1923, of whom Karl Vötterle was one. Like Hans Klein, they looked back on this time spent in “holy tranquillity far from the world” as an experience of awakening: “In Finkenstein, music revealed itself to us as a life force that that is able to overcome all pettiness, to unleash completely new forces in man, to raise him above himself. And we will never cease to proclaim this experience of music…[iii] Klein’s memoir Die Finkensteiner Singwoche (“The Singing Week at Finkenstein”) was one of the first publications of the fledgling Bärenreiter publishing house, which set out to provide institutional structures for this “proclamation”. Unlike Hensel, Karl Vötterle possessed both drive and a talent for organization and, as a bookseller’s assistant and not least as the son of a bricklayer, was skilled at getting things done and turning ideas into reality. Even before the singing week, a lack of good songbooks had led him to copy out individual songs for his small Augsburg workers’ choir, hectograph them in his parents’ living room and, since he could imagine what the “sheets would look like after a fortnight in the hands of a locksmith’s apprentice”,[iv] punch them and tie them together in a homemade folder with a piece of cord. The anthology soon attracted the interest of friends and their youth groups, and Vötterle had a bold idea: could the song sheets perhaps be printed? However, his ambitions went beyond simply reprinting something that had already been published. His aim was to publish a new song magazine, with Walther Hensel as its editor.

The singing week provided Vötterle with fresh impetus and inspiration. In Finkenstein, he came to see that for Hensel, “both because of his origins in the borderlands and because of his deepest, most personal convictions, music was not a prime concern”; it was (merely) the “main awakener of the forces slumbering within us”,[v] which Hensel considered necessary to strengthen one’s cultural identity in an all-encompassing manner. Accordingly, the publishing house that Vötterle envisaged would need to do more than just print folk songs. The singing week also provided the start-up funding for Vötterle’s venture, as participants ordered and paid for their songbook copies in advance. On top of this, Vötterle had the presence of mind not to exchange his Czech crowns back into German currency, which protected a large proportion of the fifty thousand Reichsmark he had been given by his father from the galloping devaluation of money. And an important decision was made: when Vötterle and his newfound friend Walther Sturm were resting on the roof of a parked railway carriage on their journey home, looking up at the starry sky, Vötterle told Sturm about the significance that the little star Alcor in the constellation of the Great Bear had held for him since his time as a member of the Wandervogel movement: “When dusk has fallen and the stars become visible, then the eyes of those dear to one another search for the little rider and the friends remember each other.”[vi] It was this night that the publishing house was given its name: Bärenreiter (“bear rider”).

Once back home, things moved quickly: Walther Hensel had compiled the songs for the first issue of the Finkensteiner Blätter, the Augsburg printing company Mühlberger, which Vötterle knew had experience with sheet music, provided the typesetting and printing, and on September 1 the very first work by Bärenreiter-Verlag was published. In terms of its layout, it continued to follow the concept Vötterle had developed for his privately produced song sheets. Further issues followed on a monthly basis, supplemented by poetry, fairy tales, and other ideological and religious texts, some of which – particularly from today’s perspective – are suspiciously German National in tone. Bärenreiter’s offer expanded to include a series of vocal music, Musikalisch Hausgärtlein (“A Musical Cottage Garden”), and the magazine Die Singgemeinde (“The Singing Community”). When Karl Vötterle came of age on 12 April 1924, he had his publishing house listed with the Publishers and Booksellers Association in Leipzig and registered it as a business in Augsburg. The first steps had been successfully taken.

Gudula Schütz

Title qquote taken from: Karl Vötterle, Haus unterm Stern, Kassel 41969, p. 93.

i Karl Vötterle, Das erste Jahr Bärenreiter-Verlag, Augsburg [1924], p. [3].

ii Karl Vötterle, Zur Darstellung der Gründerzeit, typescript dated 27 May 1971, p. 1 (Nachlass).

iii Hans Klein, Die Finkensteiner Singwoche, Augsburg 1924, p. 5.

iv Karl Vötterle, Haus unterm Stern, Kassel 4 1969, p. 50.

v Karl Vötterle, Fünfzig Jahre Finkensteiner Singwoche, typescript dated March 1974, p. 5 (Vötterle estate)

vi As in note 1.