Rebuilding and Expanding

The postwar years at Bärenreiter Verlag

Karl Vötterle followed the theologian Karl Barth in understanding “being allowed to start again from nothing” as the “grace of ground zero”, [i] and indeed the sense of new beginnings, of a new era, is palpable in all accounts of this period. “Away with the rubble!” – this served as a motto not only for the arduous reconstruction of Bärenreiter Verlag’s buildings, but also, figuratively speaking, for overcoming the aftermath of the Nazi period. Of course, the much-invoked “Stunde Null”, the zero hour of the end of the War, is simply a narrative, for Bärenreiter’s future could not be conceived of without its past, a past that could and would be built upon, and initially quite literally: thirty remaining or returning staff rolled up their sleeves and cleared away the debris, searching for what was still usable, and together with Vötterle – who was after all a bricklayer’s son – put a new roof on the outer walls of the so-called “new building” by Christmas 1945. With professional support, but under the adverse conditions of the general postwar shortages, Bärenreiter’s team erected makeshift buildings, pressed ahead with interior work, and organised furniture and machinery; large vegetable fields established in the publishing house’s garden helped to improve everyone’s food supply. Thanks to a talent for improvisation, the family business’s team spirit and, last but not least, Vötterle’s trust in God, Bärenreiter was able to start selling antiquarian books in 1945. Part of this stock had been rescued from a bricked-up Bärenreiter cellar; the rest came from the holdings of a library Bärenreiter had purchased or had been gifted by friends of the publishing house. After a publishing licence was granted to chief editor Richard Baum in January 1946 (Karl Vötterle was not allowed to take over until the conclusion of his denazification proceedings in late 1947), Bärenreiter’s first postwar publishing projects – luckily viewed favourably by U.S. “Information Control” – took on concrete shape. In particular, Bärenreiter’s magazines such as Die Neue Schau and Musik und Kirche seemed predestined to “serve the publishing house’s mission” by opening up “sufficient strength to rebuild”[ii] in postwar Germany; the same applied to the newly added branch of amateur plays. Despite gifts received from abroad, there was still not enough paper to print music, and so initially holdings from Bärenreiter’s archive that had been stored in a countryside brickyard and had thus survived the War were offered for hire.

There was also a fresh start in Karl Vötterle’s private life: in March 1945, he had found a new partner and a mother for his four children in Hildegard Preime, the widow of the art historian and Bärenreiter author Eberhard Preime, who had been killed in action in the War. Two and a half years later, on 27 November 1947, Hildegard gave birth to a daughter, Barbara. It was Barbara who took over the management of Bärenreiter Verlag after her father’s death in 1975.

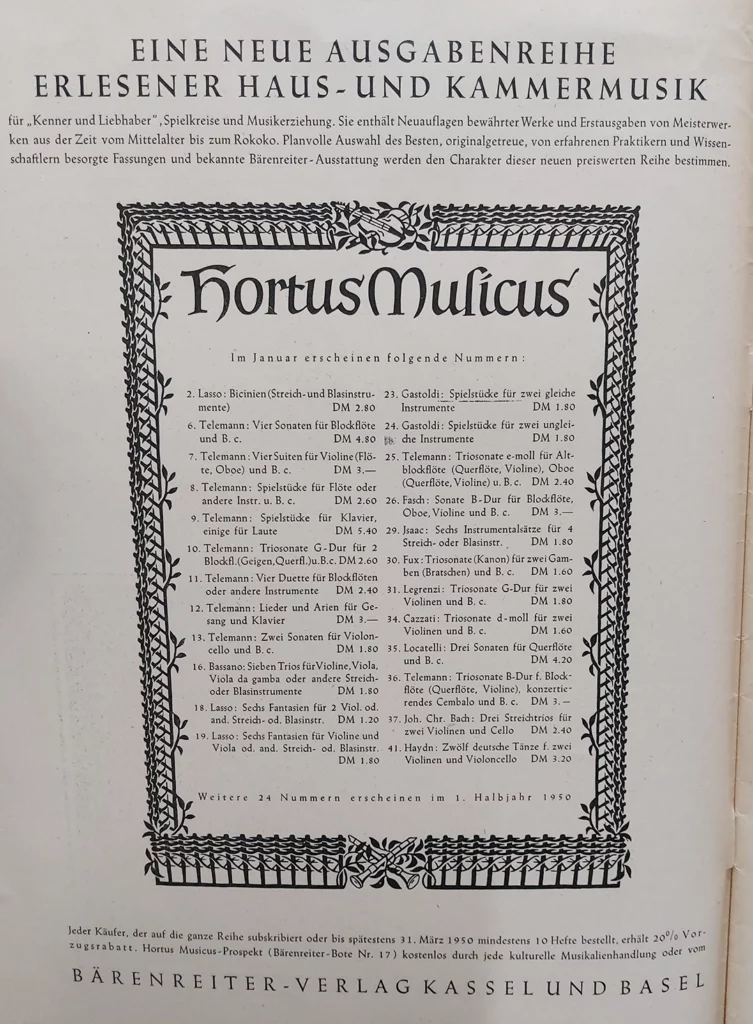

By 1947, the number of Bärenreiter’s employees had already risen to 86; step by step, older titles were reissued and the catalogue expanded. In 1950, a supplement to the 1949 catalogue – which was a “torso” in that it contained “only a small part of the publications that have appeared in the twenty-five years since the founding of Bärenreiter Verlag”[iii] – appeared in print, listing more than 200 new titles published between June 1949 and September 1950 as well as reprints: the popular Quempas, the works of Heinrich Schütz and keyboard music by Johann Sebastian Bach, as well as new names such as Helmut Bornefeld, Willy Burkhard, Johannes Driessler, Christian Lahusen, Hans Friedrich Micheelsen and Siegfried Reda, the first issues of the Hortus musicus series, and above all the first four volumes of the encyclopaedia Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart. The “great plans” that Vötterle had taken “comfort in”[iv] during the Nazi era were by no means mere romantic fantasy. With determination and an excellent feel for useful contacts, as well as a talent for making decisions at just the right moment, Vötterle had already set the realisation of these plans in motion during the War. Together with Friedrich Blume, a musicologist from Kiel well connected during the Nazi period, he not only prepared and published the MGG, but also founded the Gesellschaft für Musikforschung (Society for Music Research) in 1947 and collaborated strategically with Blume on the preparation and execution of numerous complete editions. While the first project, the Complete Works of Gluck, had still been supported by the National Socialists, the editions of the works of J. S. Bach, Telemann, Mozart, and Handel were created in the spirit of the postwar period, when the experience of the destruction of cultural assets was still vividly present and the desire to preserve and order what had been handed down was a driving force. In his programmatic essay Die Stunde der Gesamtausgabe (The Hour of the Complete Edition), Vötterle pointed out that such projects “point to the future in terms of the essence of publishing.”[v] Looking back, this certainly proved true for the area of complete editions and the resulting expansion of Bärenreiter’s Urtext portfolio; but Bärenreiter also led the way in scholarly and political terms, successfully overcoming international borders, especially those of the Iron Curtain. By the time Vötterle received the commission for the New Bach Edition from West Germany’s President Theodor Heuss on 3 March 1951, Bärenreiter had become something that its founder had not initially intended: a world-class music publisher.

Gudula Schütz

[i] Karl Vötterle, Haus unterm Stern, Kassel 41969, p. 186.

[ii] Der Bärenreiter-Bote, no. 11, Kassel 1947, p. [17] and [13].

[iii] Gesamtverzeichnis, Kassel and Basel 1949, S. [3].

[iv] Vötterle, Bärenreiter-Verlag Kassel, Entwicklungsgeschichte, typescript 27 May 1971 (Vötterle estate).

[v] Musica vol. 10, no. 1, 1956, p. 35.